近年来,全球甲状腺癌发病率逐渐升高,在我国城市为第5位高发癌症,在浙江省甚至位居第二[1]。根据病理分型,甲状腺癌主要分为分化型甲状腺癌(differentiated thyroid carcinoma,DTC)、髓样癌(medullary thyroid carcinoma,MTC)和未分化癌(anaplastic thyroid carcinoma,ATC),其中DTC进一步分为乳头状癌(papillary thyroid carcinoma,PTC)和滤泡癌(follicular thyroid carcinoma,FTC)。精准的肿瘤分期和风险分层对改善生存、降低复发、避免过度治疗具有重要意义。目前,常见的甲状腺癌预后情况的评估体系主要包括:美国癌症联合委员会(American Joint Commission on Cancer,AJCC)肿瘤-淋巴结-转移(tumor-nodes-metastases,TNM)分期、AGES(age,grade,extent,size)分层、AMES(age,metastases,extent of disease,size)分层、MACIS(metastases,age,completeness of resection,invasion locally,size)分期等[2]。其中,TNM分期是应用最广泛的预后评估系统之一,已被纳入最近发布的世界卫生组织(World Health Organization,WHO)的甲状腺肿瘤分级制度中。

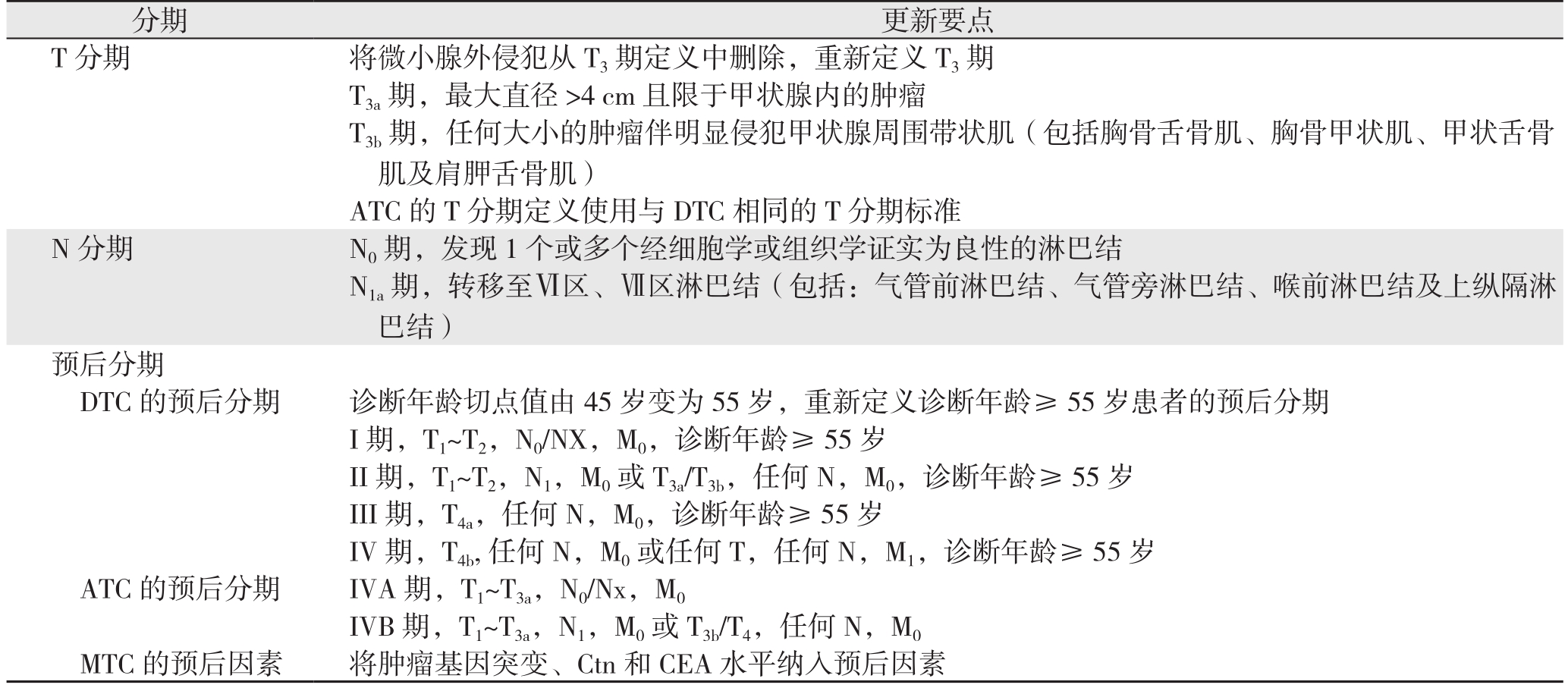

2016年AJCC发布的第8版甲状腺癌TNM分期系统于2018年1月1日正式投入临床使用,与7版[3]相比,第8版[4]主要的更新要点如下(表1)。⑴ T分期:重新定义T3期,去除微小腺外侵犯(minimal extrathyroidal extension/minor extrathyroidal extension,mETE);ATC将使用DTC的T分期标准;⑵ N分期:将VII区淋巴结转移纳入N1a期;⑶ 预后分期:DTC,将诊断年龄切点值由45岁变更为55岁;去除mETE及转移淋巴结位置对诊断年龄≥55岁(老年)患者预后分期的影响;ATC,重新定义ATC的IVA及IVB期;MTC,将MTC预后分期列为独立章节,并将肿瘤基因突变、降钙素(calcitonin,Ctn)和癌胚抗原(carcinoembryonic antigen,CEA)水平纳入预后因素。第8版中还提出:在甲状腺癌术后随访的前4个月如获得更新数据,可对肿瘤重新评估。

表1 第8版TNM分期系统更新要点总结

Table1 Summary of the essential points of the updates in the 8th TNM staging system

分期 更新要点T分期 将微小腺外侵犯从T3期定义中删除,重新定义T3期T3a期,最大直径>4 cm且限于甲状腺内的肿瘤T3b期,任何大小的肿瘤伴明显侵犯甲状腺周围带状肌(包括胸骨舌骨肌、胸骨甲状肌、甲状舌骨肌及肩胛舌骨肌)ATC的T分期定义使用与DTC相同的T分期标准N分期 N0期,发现1个或多个经细胞学或组织学证实为良性的淋巴结N1a期,转移至Ⅵ区、Ⅶ区淋巴结(包括:气管前淋巴结、气管旁淋巴结、喉前淋巴结及上纵隔淋巴结)预后分期DTC的预后分期 诊断年龄切点值由45岁变为55岁,重新定义诊断年龄≥55岁患者的预后分期I期,T1~T2,N0/NX,M0,诊断年龄≥ 55 岁II期,T1~T2,N1,M0或 T3a/T3b,任何 N,M0,诊断年龄≥ 55 岁III期,T4a,任何N,M0,诊断年龄≥55岁IV期,T4b,任何N,M0或任何T,任何N,M1,诊断年龄≥55岁ATC 的预后分期 IVA 期,T1~T3a,N0/Nx,M0 IVB 期,T1~T3a,N1,M0或 T3b/T4,任何 N,M0 MTC的预后因素 将肿瘤基因突变、Ctn和CEA水平纳入预后因素

1 T分期的更新要点及评估效果

1.1 重新定义T3分期

2002年首次将mETE纳入T分期标准,即:肿瘤最大径>4 cm且限于甲状腺内或无论肿瘤大小伴有mETE(胸骨甲状肌或甲状腺周围软组织)者,属T3期。第7版延用这一定义,而第8版则将其删除,认为mETE不再影响T分期甚至预后分期。T3期重新定义为:T3a,肿瘤最大径>4 cm且限于甲状腺内;T3b,无论肿瘤大小伴明显侵犯甲状腺周围带状肌,即胸骨舌骨肌、胸骨甲状肌、甲状舌骨肌和肩胛舌骨肌。

第8版将mETE删除的主要原因体现在两方面:一方面,甲状腺被膜具有不完整性且正常甲状腺内可能含有脂肪和骨骼肌组织,致无法明确界定mETE;另一方面,mETE并非甲状腺癌预后的独立风险因素[5-7]。该分期发布后,引起了广泛争议,各方学者纷纷提出不同观点,认为mETE可增加肿瘤复发风险[8-10]。然而,由于上述研究中侵犯甲状腺周围带状肌仍被定义为mETE,故无法排除结果中侵犯带状肌对预后的影响。笔者认为,造成争议的主要原因是学者们对mETE的定义缺乏明确的认识,mETE应定义为:显微镜下可见的癌细胞从甲状腺组织到周围脂肪组织的任何扩散,无论该甲状腺被膜是否完整。目前,进一步精确评估mETE的预后情况很有必要,对存在mETE的患者我们提倡术后进行积极地随访。

1.2 重新定义ATC的T分期

第7版将所有ATC均定义为T4期,并依据是否限于甲状腺内分为两个子分类。而第8版中ATC则使用DTC的T分期标准,纳入原发肿瘤大小作为预测指标。这一变化表明肿瘤大小将影响ATC患者的预后,但目前尚缺乏相关研究予以验证,2017年美国国家综合癌症网络(National Comprehensive Cancer Network,NCCN)指南[11]仍使用第7版的ATC分期标准。笔者认为,精细化后的T分期标准,可为更加精确的预后分期提供依据。而不同大小的ATC预后是否存在差异,仍需进一步评估。

2 N分期的更新要点及评估效果

第8版将N0期定义为:发现1个或多个经细胞学或组织学证实为良性的淋巴结;N1a期则包括转移至Ⅵ、Ⅶ区的淋巴结。Ⅶ区淋巴结即上纵膈淋巴结,与Ⅵ区低位淋巴结解剖相连续,主要依靠外科医生手术区分。在之前的分期系统中,Ⅶ区淋巴结转移属于N1b期。针对这一变化,学者们表示赞同[12-13],并认为此改变可消除病理报告对区分Ⅵ、Ⅶ区淋巴结时存在的不确定性。尽管尚缺乏有力证据,但仍可认为此修改提高了N分期的准确性,更利于精准的甲状腺癌管理。

3 预后分期的更新要点及评估效果

3.1 DTC的预后分期

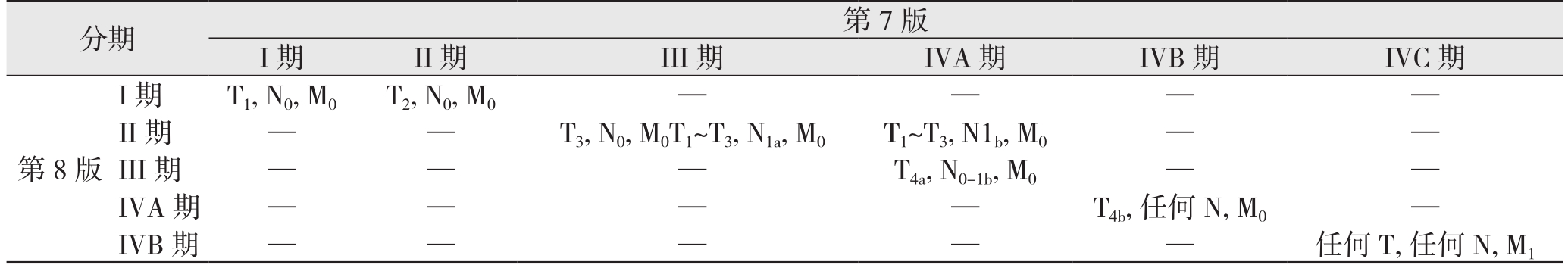

3.1.1 预后分期下调 与第7版比较,第8版中老年DTC患者的预后分期发生显著变化(表2),主要体现在以下几个方面:⑴ 更改年龄切点值,使部分诊断年龄为45~55岁的患者由III、IV期下调至I、II期;⑵ 第7版中存在mETE者被归入III、IVA期,而在第8版中mETE不再影响老年患者的预后分期,该部分患者将下调至I、II期;⑶ 伴颈部淋巴结转移且肿瘤限于甲状腺内者由III、IVA期降至II期;⑷ 出现皮下软组织、喉、气管、食道或喉返神经等任一项侵犯者,由IVA期降至III期;⑸ 出现椎前筋膜侵犯、包绕颈动脉或纵隔血管者由IVB期降至IVA期;⑹ 远处转移者由IVC期降至IVB期,并将IVC期删除。综上,这些变化的最终结果是将大多数患者归为较低的预后分期,近期一项国内研究对此同样表示赞同[14]。然而,值得注意的是,分期下调可能更多地反映了相对低风险组患者良好的生存结局,但并不代表复发风险同样降低[15-18]。因此,笔者建议对分期下调的患者术后积极随访。

表2 第7版与第8版对老年DTC患者的预后分期比较

Table2 Comparison of the prognostic stages for elderly DTC patients between the 7th and 8th edition

分期 第7版I期 II期 III期 IVA期 IVB期 IVC期第8版I期T1, N0, M0T2, N0, M0 — — — —II期 — — T3, N0, M0T1~T3, N1a, M0 T1~T3, N1b, M0 — —III期 — — — T4a, N0-1b, M0 — —IVA期 — — — — T4b, 任何N, M0 —IVB期 — — — — — 任何T, 任何N, M1

3.1.2 更改诊断年龄切点值 自第2版发布后,45岁一直是该系统中DTC患者诊断年龄的切点值。期间,多位学者[19-20]研究表明DTC的预后与年龄存在相关性,年轻患者的预后较老年患者更好,但并未找到明确的年龄切点值。最近,一些学者[21-23]则支持将诊断年龄为55岁作为预后评估的最佳切点值。第8版对此观点表示赞同,其改动主要基于2篇研究[24-25]。在第8版发布后,Kim等[16]指出,将年龄切点值提高到55岁不仅在临床上合适,在基因层面上也较为合理。Verburg等[26]同样认为此变化可能提高第8版预测生存的能力。由此可见,诊断年龄切点值的更改,可更为准确地预测DTC患者的生存情况,但仍建议对诊断年龄在45~55岁之间的DTC患者术后进行密切地随访。

3.1.3 去除淋巴结转移位置的影响 在第7版中,诊断年龄≥45岁出现中央组(N1a期)或侧颈部(N1b期)淋巴结转移者,分别属于III、IV期。然而,第8版中,转移淋巴结位置将不再影响老年患者的预后分期,存在淋巴结转移者均为II期(无远处转移情况下)。第8版提出这一变化是基于淋巴结位置和生存结果之间的相关性可能被淋巴结大小和数量的影响所混淆,并将其他相关指标(包括转移淋巴结数目、比值、最大径、转移灶最大径及淋巴结外侵犯)列为潜在的预后影响因素。然而,有重要证据表明N1b期的预后明显比N1a期差,侧颈淋巴结转移是死亡的独立风险因素[27-29]。更有研究[30-32]证实淋巴结转移相关指标与DTC预后相关。笔者认为,与N1a期患者相比,N1b期除转移淋巴结位置不同外,存在相对更大的淋巴结最大径、更多的淋巴结数、更大可能的淋巴结外侵犯,这可能是导致N1b期预后差的主要原因。将来是否有可能将淋巴结转移相关指标组合,共同纳入预后分期,尚待考虑。

3.2 ATC的预后分期

第7版中,颈部淋巴结转移并不影响ATC的预后分期,而第8版则将其纳入作为预后的预测指标。将IVA期定义为限于甲状腺内不伴颈部淋巴结转移;IVB期则包含限于甲状腺内伴颈部淋巴结转移或无论肿瘤大小有宏观甲状腺外侵犯者;IVC期定义同第7版,即有远处转移者。第8版认为有颈部淋巴结转移的ATC预后较差,而偶发、体积较小并可完全切除者则显示更好的预后。目前尚缺乏相关研究,但新的预后分期可能有助于更为精准地评估ATC的预后情况,并为其治疗策略提供更为合理的依据。

3.3 MTC的预后因素

对于MTC,第8版认为其预后可能与基因突变有关,Ctn和CEA则具有潜在的价值,故将基因突变、Ctn及CEA水平纳入预后因素。且2017年NCCN[11]同样将上述三者纳入MTC管理指南中,Guilmette等[33]甚至建议对MTC患者常规行基因检测。然而,值得注意的是,Ctn和CEA并非特异性标志物,不同检测方法的参考范围也不尽相同,且检测结果存在一定的假阳性与假阴性。此外,在我国对MTC患者常规行基因检测尚有一定难度。故针对我国国情,结合影像学改变及Ctn和CEA检测,可为MTC的管理提供指导意义。同时,进一步评估基因突变、Ctn及CEA水平对MTC预后分期的影响可能较为必要。

4 第8版的整体评价

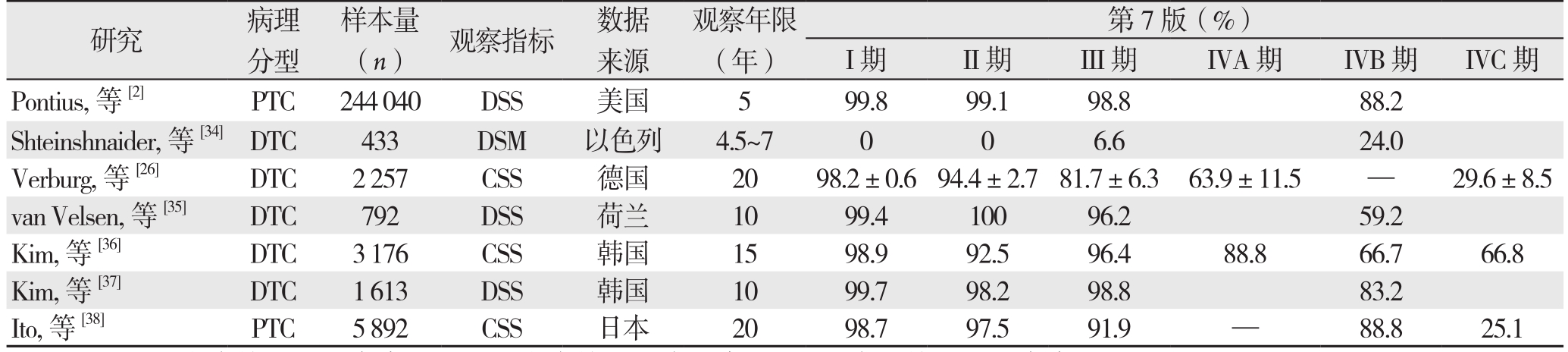

自第8版发布以来,多位学者就第7、8版对甲状腺癌预后情况的预测能力进行了比较和验证,各自提出不同观点(表3)。

表3 第7版与第8版分期系统对预后的评估效果比较

Table3 Comparison of the assessment effectiveness on prognosis between the 7th and 8th edition

注:DSS:疾病特异性生存率;DSM:疾病特异性病死率;CSS:病因特异性生存率

Note: DSS: disease-specific survival; DSM: disease-specific mortality; CSS: cause-specific survival

第7版(%)I期 II期 III期 IVA期 IVB期 IVC期Pontius,等[2] PTC 244040 DSS 美国 5 99.8 99.1 98.8 88.2 Shteinshnaider,等[34]DTC 433 DSM 以色列 4.5~7 0 0 6.6 24.0 Verburg,等[26] DTC 2257 CSS 德国 20 98.2±0.694.4±2.781.7±6.3 63.9±11.5 — 29.6±8.5 van Velsen,等[35] DTC 792 DSS 荷兰 10 99.4 100 96.2 59.2 Kim,等[36] DTC 3176 CSS 韩国 15 98.9 92.5 96.4 88.8 66.7 66.8 Kim,等[37] DTC 1613 DSS 韩国 10 99.7 98.2 98.8 83.2 Ito,等[38] PTC 5892 CSS 日本 20 98.7 97.5 91.9 — 88.8 25.1研究 病理分型样本量(n) 观察指标 数据来源观察年限(年)

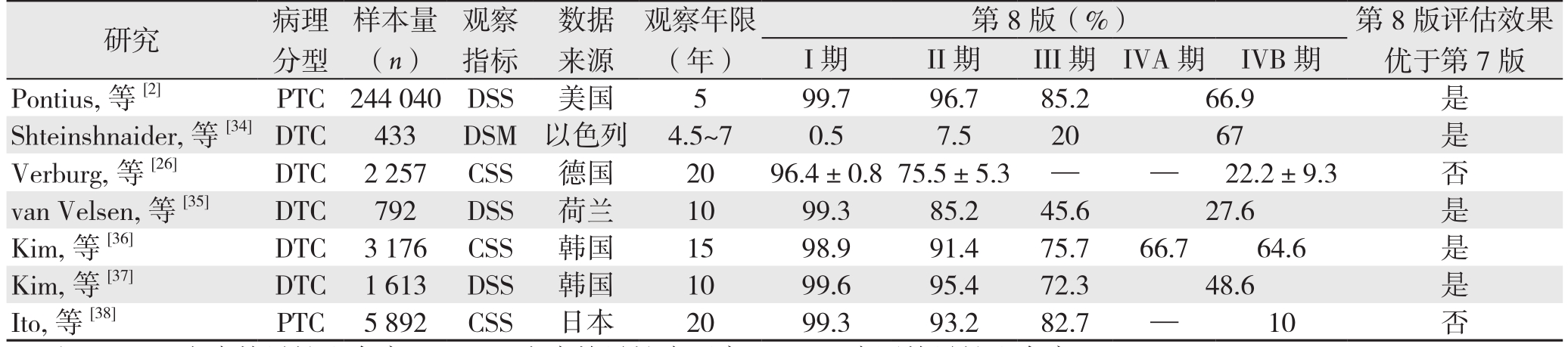

表3 第7版与第8版分期系统对预后的评估效果比较(续)

Table3 Comparison of the assessment effectiveness on prognosis between the 7th and 8th edition (continued)

注:DSS:疾病特异性生存率;DSM:疾病特异性病死率;CSS:病因特异性生存率

Note: DSS: disease-specific survival; DSM: disease-specific mortality; CSS: cause-specific survival

I期 II期 III期 IVA期 IVB期Pontius,等[2] PTC 244040 DSS 美国 5 99.7 96.7 85.2 66.9 是Shteinshnaider,等[34]DTC 433 DSM 以色列 4.5~7 0.5 7.5 20 67 是Verburg,等[26] DTC 2257 CSS 德国 20 96.4±0.875.5±5.3 — — 22.2±9.3 否van Velsen,等[35] DTC 792 DSS 荷兰 10 99.3 85.2 45.6 27.6 是Kim,等[36] DTC 3176 CSS 韩国 15 98.9 91.4 75.7 66.7 64.6 是Kim,等[37] DTC 1613 DSS 韩国 10 99.6 95.4 72.3 48.6 是Ito,等[38] PTC 5892 CSS 日本 20 99.3 93.2 82.7 — 10 否研究 病理分型样本量(n)观察指标数据来源观察年限(年)第8版(%) 第8版评估效果优于第7版

大部分学者对第8版持积极态度。很多研究证实,与第7版相比,应用第8版时,各预后分期之间的生存率(或病死率)呈现较高的分离度,被纳入III、IV期的患者,其预后较第7版中相同分期的患者差,表明该系统确实能更好地预测DTC患者的生存情况[2,15-16,34-37,39]。同时第8版提供了更有意义的预后风险分层,且其修改可能会减少对降期患者的辅助治疗,从而避免过度治疗[2,5]。此外,van Velsen等[35]还指出,第8版对PTC和FTC不同预后分期的生存率具有相同的评估效能,表明该系统对DTC两个子分类的预测能力良好。由此,笔者认为针对DTC患者术后生存情况的预测,第8版优于第7版,可为临床医生提供更为合理的治疗决策。

然而,一些学者对此也提出了不同观点。Verburg等[26,38]采用PVE(proportion of variation explained)分析分别评估两个系统效能后,认为无法得出第8版明显优于第7版的结论。但目前PVE分析并未得到广泛认可,故此结论尚需进一步验证。关于MTC,Adam等[40]认为现有的分期标准对预后的预测能力相对较差,并建议重新考虑。由于ATC的罕见性,应用第8版评估ATC预后情况的相关研究并不多。虽然目前部分专家学者针对第8版提出争议,但由于样本量相对较少、数据来源较为局限,循证医学证据不足,故并不足以说明第8版的应用价值较第7版差。

综上,尽管学术界对第8版尚存较多争议,但其仍是一个将临床分子信息及病理解剖信息整合的更为精准、合理的分期系统。笔者认为,较之第7版,第8版能更精确地评估DTC患者的死亡风险,但TNM的低分期并不等同于复发风险分层的低危,仍需术后密切随访。从社会经济角度出发,合理的降期可适当地避免过度诊疗,降低不必要的医疗损耗;同时,也可减轻患者的心理精神压力和经济负累,提升其生活质量。然而,由于数据的缺乏及来源的局限性,该系统对MTC及ATC预后情况的预测能力尚无法评估,同样不能明确其是否适用于所有人群。以我国为例,由于既往国内很多中心对TNM分期不够重视或应用不甚规范,致使相关研究较为缺乏,因此,第8版在我国的应用价值如何亟需多中心数据积极验证和评估。期待接下来,我国甲状腺学者能够开展多中心合作,规范化应用TNM分期系统,积累患者术后长期随访资料,为甲状腺癌的分层化管理及个体化诊治提供更多数据。

[1] 程若川, 刘文. 中国甲状腺癌术后随访和临床研究现状反思[J].中国普通外科杂志, 2017, 26(11):1375–1382. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005–6947.2017.11.002.Cheng RC, Liu W. Reflections on current problems in postoperative follow-up and clinical study of thyroid carcinoma in China[J].Chinese Journal of General Surgery, 2017, 26(11):1375–1382.doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005–6947.2017.11.002.

[2] Pontius LN, Oyekunle TO, Thomas SM, et al. Projecting Survival in Papillary Thyroid Cancer: A Comparison of the Seventh and Eighth Editions of the American Joint Commission on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control Staging Systems in Two Contemporary National Patient Cohorts[J]. Thyroid, 2017, 27(11):1408–1416. doi:10.1089/thy.2017.0306.

[3] Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed[M]. New York,NY: Springer, 2010.

[4] Amin MB, edge SB, greene FL, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed[M]. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

[5] Domínguez JM, Nilo F, Martínez MT, et al. Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: characteristics at presentation, and evaluation of clinical and histological features associated with a worse prognosis in a Latin American cohort[J]. Arch Endocrinol Metab, 2018,62(1):6–13. doi: 10.20945/2359–3997000000013.

[6] Hay ID, Johnson TR, Thompson GB, et al. Minimal extrathyroid extension in papillary thyroid carcinoma does not result in increased rates of either cause-specific mortality or postoperative tumor recurrence[J]. Surgery, 2016, 159(1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.05.046.

[7] Woo CG, Sung CO, Choi YM, et al. Clinicopathological Significance of Minimal Extrathyroid Extension in Solitary Papillary Thyroid Carcinomas[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2015, 22(Suppl 3):S728–733. doi: 10.1245/s10434–015–4659–0.

[8] Tran B, Roshan D, Abraham E, et al. An Analysis of The American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th Edition T Staging System for Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2018,103(6):2199–2206. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017–02551.

[9] Yin DT, Yu K, Lu RQ, et al. Prognostic impact of minimal extrathyroidal extension in papillary thyroid carcinoma[J].Medicine (Baltimore), 2016, 95(52):e5794. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005794.

[10] Diker-Cohen T, Hirsch D, Shimon I, et al. Impact of Minimal Extra-Thyroid Extension in Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2018. doi:10.1210/jc.2018–00081. [Epub ahead of print]

[11] NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in oncology. Thyroid carcinoma. Version 2.2017[S]. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/thyroid.pdf.

[12] Wang LY, Palmer FL, Thomas D, et al. Level 7 disease does not confer worse outcome than level 6 disease in differentiated thyroid cancer[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2015, 22(2):441–445. doi: 10.1245/s10434–014–4045–3.

[13] Perrier ND, Brierley JD, Tuttle RM. Differentiated and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: Major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(1):55–63. doi: 10.3322/caac.21439.

[14] 刘媛超, 丁汉, 王义增, 等. 甲状腺癌AJCC/TNM分期系统第8版与第7版在分化型甲状腺癌诊治中应用比较[J]. 中国实用外科杂志, 2018, 38(6):639–642. doi: 10.19538/j.cjps.issn1005–2208.2018.06.13.Liu YC, Ding H, Wang YZ, et al. Application and comparison of AJCC/TNM staging system in the eighth and seventh editions for differentiated thyroid cancer[J]. Chinese Journal of Practical Surgery, 2018, 38(6):639–642. doi: 10.19538/j.cjps.issn1005–2208.2018.06.13.

[15] Ghaznavi SA, Ganly I, Shaha AR, et al. Using the American Thyroid Association Risk-Stratification System to Refine and Individualize the American Joint Committee on Cancer Eighth Edition Disease-Specific Survival Estimates in Differentiated Thyroid Cancer[J]. Thyroid, 2018, 28(10):1293–1300. doi: 10.1089/thy.2018.0186.

[16] Kim K, Kim JH, Park IS, et al. The Updated AJCC/TNM Staging System for Papillary Thyroid Cancer (8th Edition): From the Perspective of Genomic Analysis[J]. World J Surg, 2018. doi:10.1007/s00268–018–4662–2. [Epub ahead of print]

[17] Rosario PW. Eighth edition of AJCC staging for differentiated thyroid cancer: Is stage I appropriate for T4/N1b patients aged 45–55 years?[J]. Endocrine, 2017, 56(3):679–680. doi: 10.1007/s12020–017–1288–3.

[18] Tuttle RM, Haugen B, Perrier ND. Updated American Joint Committee on Cancer/Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging System for Differentiated and Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer (Eighth Edition):What Changed and Why?[J]. Thyroid, 2017, 27(6):751–756. doi:10.1089/thy.2017.0102.

[19] Orosco RK, Hussain T, Brumund KT, et al. Analysis of age and disease status as predictors of thyroid cancer-specific mortality using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database[J].Thyroid, 2015, 25(1):125–132. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0116.

[20] Adam MA, Thomas S, Hyslop T, et al. Exploring the Relationship Between Patient Age and Cancer-Specific Survival in Papillary Thyroid Cancer: Rethinking Current Staging Systems[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2016, 34(36):4415–4420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.9372.

[21] Nixon IJ, Wang LY, Migliacci JC, et al. An International Multi-Institutional Validation of Age 55 Years as a Cutoff for Risk Stratification in the AJCC/UICC Staging System for Well-Differentiated Thyroid Cancer[J]. Thyroid, 2016, 26(3):373–380.doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0315.

[22] Kim M, Kim YN, Kim WG, et al. Optimal cut‐off age in the TNM Staging system of differentiated thyroid cancer: is 55 years better than 45 years?[J]. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2017, 86(3):438–443. doi:10.1111/cen.13254.

[23] Hendrickson-Rebizant J, Sigvaldason H, Nason RW, et al.Identifying the most appropriate age threshold for TNM stage grouping of well‐differentiated thyroid cancer[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol,2015, 41(8):1028–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.04.014.

[24] Ganly I, Nixon IJ, Wang LY, et al. Survival from Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: What Has Age Got to Do with It?[J]. Thyroid,2015, 25(10):1106–1114. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0104.

[25] Nixon IJ, Kuk D, Wreesmann V, et al. Defining a Valid Age Cutoffin Staging of Well-Differentiated Thyroid Cancer[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2016, 23(2):410–415. doi: 10.1245/s10434–015–4762–2.

[26] Verburg FA, Mäder U, Luster M, et al. The effects of the Union for International Cancer Control/American Joint Committee on Cancer Tumour, Node, Metastasis system version 8 on staging of differentiated thyroid cancer: a comparison to version 7[J]. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2018, 88(6):950–956. doi: 10.1111/cen.13597.

[27] Kim M, Jeon MJ, Oh HS, et al. Prognostic Implication of N1b Classification in the Eighth Edition of the Tumor‐Node‐Metastasis Staging System of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer[J]. Thyroid, 2018,28(4):496–503. doi: 10.1089/thy.2017.0473.

[28] Jeon MJ, Kim WG, Kim TH, et al. Disease-Specific Mortality of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Patients in Korea: A Multicenter Cohort Study[J]. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul), 2017, 32(4):434–441.doi: 10.3803/EnM.2017.32.4.434.

[29] Kim HI, Kim K, Park SY, et al. Refining the eighth edition AJCC TNM classification and prognostic groups for papillary thyroid cancer with lateral nodal metastasis[J]. Oral Oncol, 2018, 78:80–86.doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.01.021.

[30] Wu MH, Shen WT, Gosnell J, et al. Prognostic significance of extranodal extension of regional lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid cancer[J]. Head Neck, 2015, 37(9):1336–1343. doi:10.1002/hed.23747.

[31] Kim HI, Kim TH, Choe JH, et al. Restratification of survival prognosis of N1b papillary thyroid cancer by lateral lymph node ratio and largest lymph node size[J]. Cancer Med, 2017,6(10):2244–2251. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1160.

[32] Adam MA, Pura J, Goffredo P, et al. Presence and Number of Lymph Node Metastases Are Associated With Compromised Survival for Patients Younger Than Age 45 Years With Papillary Thyroid Cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2015, 33(21):2370–2375. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.59.8391.

[33] Guilmette J, Nosé V. Hereditary and familial thyroid tumours[J].Histopathology, 2018, 72(1):70–81. doi: 10.1111/his.13373.

[34] Shteinshnaider M, Muallem Kalmovich L, Koren S, et al.Reassessment of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Patients Using the Eighth TNM/AJCC Classification System: A Comparative Study[J].Thyroid, 2018, 28(2):201–209. doi: 10.1089/thy.2017.0265.

[35] van Velsen EFS, Stegenga MT, van Kemenade FJ, et al. Comparing the Prognostic Value of the Eighth Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Tumor Node Metastasis Staging System Between Papillary and Follicular Thyroid Cancer[J]. Thyroid, 2018,28(8):976–981. doi: 10.1089/thy.2018.0066.

[36] Kim TH, Kim YN, Kim H I, et al. Prognostic value of the eighth edition AJCC TNM classification for differentiated thyroid carcinoma[J]. Oral Oncol, 2017, 71:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.06.004.

[37] Kim M, Kim WG, Oh H S, et al. Comparison of the Seventh and Eighth Editions of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging System for Differentiated Thyroid Cancer[J]. Thyroid, 2017,27(9):1149–1155. doi: 10.1089/thy.2017.0050.

[38] Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Hirokawa M, et al. Prognostic value of the 8th edition of the tumor‐node‐metastasis classification for patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: a single-institution study at a highvolume center in Japan[J]. Endocr J, 2018, 65(7):707–716. doi:10.1507/endocrj.EJ18–0019.

[39] Suh S, Kim YH, Goh TS, et al. Outcome prediction with the revised American joint committee on cancer staging system and American thyroid association guidelines for thyroid cancer[J]. Endocrine,2017, 58(3):495–502. doi: 10.1007/s12020–017–1449–4.

[40] Adam MA, Thomas S, Roman SA, et al. Rethinking the Current American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM Staging System for Medullary Thyroid Cancer[J]. JAMA Surg, 2017, 152(9):869–876.doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1665.