头静脉弓狭窄(cephalic arch stenosis,CAS)是导致头静脉-肱动脉内瘘(brachiocephalic fistula,BCF)失功的重要原因,发生率有文献报道16%~30%[1-2]。目前的处理方法主要有经皮球囊扩张成形术(percutaneous transluminal angioplasty,PTA)、支架植入术、头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位以及内瘘缩窄/限流术等[1-4]。腔内治疗技术如PTA及支架植入术均有再狭窄,需要反复干预的风险[5-6],因此头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位、限流术也成为部分患者的选择[3-4]。笔者近几年采用头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位联合内瘘缩窄术治疗高流量BCF合并CAS患者,获得了较好的临床效果。

1 资料与方法

1.1 临床资料

选择2014年1月—2017年6月,因CAS入院的患者。入选标准:⑴ 年龄满18岁,同意参加本研究;⑵ 以头静脉-肱动脉内瘘作为透析通路;⑶ 病史、体检提示CAS相关临床症状需要处理:内瘘压力增高、止血困难、上臂可见内瘘瘤样增生、透析中静脉压进行性增加等;⑷ 超声评估内瘘流量>1 500 mL/min[3];⑸ 静脉造影证实CAS,狭窄比>50%;⑹ 彩超及造影证实同侧腋静脉及同侧中心静脉通畅,未见狭窄或血栓等,拟吻合的贵要(腋)静脉内径≥4.0mm;⑺ 既往行头静脉弓PTA治疗,再狭窄的时间间隔≤3个月。同时符合7条入选标准的才能入组。排除标准:⑴ 肱动脉-头静脉人工血管移植物内瘘患者;⑵ 术前彩超及造影提示同侧腋静脉及中心静脉狭窄或闭塞患者;⑶ 患者有其他基础疾病,如晚期肿瘤,严重凝血功能障碍,严重心、肺功能不全不耐受行该种手术的患者;⑷ 因动脉系统疾导致的通路相关性缺血综合征;⑸ 非肱动脉-头静脉内瘘;⑹ 拒绝行该手术方案的。符合以上一条的,即排除。对于内瘘闭塞性患者,如因CAS导致闭塞,先采取其他方式(如溶栓、PTA、取栓等)开通血管,评估完成后符合标准再行头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位联合内瘘缩窄术。

1.2 方法

1.2.1 头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位联合内瘘缩窄术 臂丛神经阻滞或全麻,局部消毒铺巾,在肘部游离原内瘘吻合口,在上臂上段游离头静脉及贵要(腋)静脉、肱动脉。静脉推注肝素盐水20 mg全身肝素化,备用。暂时阻断肱动脉血流,将头静脉近心端结扎,远心端经过皮下隧道与贵要(腋)静脉行端侧吻合。恢复动脉供血,检查内瘘无渗血。再次阻断动脉血流,切开原吻合口后方1 cm流出道静脉10~20 mm,用2.9~3.5 mm内径的尿管作为支撑,剪除多余血管壁(包括钙化部分),用6-0血管缝合线将静脉连续缝合,将内瘘口后方静脉缩窄至3.0~4.0 mm。再次恢复动脉供血,检查内瘘吻合口及上臂吻合口无明显渗血。触诊内瘘震颤良好。依次缝合皮下组织及皮肤。无菌敷料包扎伤口。

1.2.2 术后监测及干预 超声监测:超声(诊断仪为飞利浦公司的IE33,探头频率4~12 MHz)。所有患者在术后24 h及3个月开始超声监测计划,每3个月1次。超声监测到显著性性狭窄[7-9]时考虑行DSA静脉造影,并决定是否需要干预。所有的超声评估由同一位手术医生与超声医生共同进行,残余管径及血流量连续测量3次,取平均值。超声探测显著性血管狭窄的定义为[7-9]:⑴ 血管内径下降>50%;⑵ 狭窄处峰值流速(peak systolic velocity,PSV)增加>2倍;⑶ 狭窄处PSV>400 cm/s, Qa下降>25%或Qa<600 mL/min;⑷ 残余管径<2 mm。

1.2.3 干预措施 入选患者在超声监测达到显著性狭窄后行干预措施。腔内血管治疗包括: PTA、腔内溶栓、Fogarty取栓等。开放手术治疗包括:再次缩窄吻合口、补片、切开取栓等。

1.2.4 终点事件 初级终点:初级通畅率,定义为行头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位联合内瘘缩窄术后到任何其他需要干预措施的时间,用Kaplan-Meier生存分析表示。次级终点:⑴ 次级通畅率,定义为行首次行头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位联合内瘘缩窄术后到发生下列情况的时间:医生或患者决定采取其他血管通路,包括改用带CUFF中心静脉导管(tunneled cuffed catheter,TCC),或改腹膜透析(peritoneal dialysis,PD)或其他类型动静脉内瘘;⑵ 患者死亡、放弃透析或失访。

1.3 统计学处理

全部数据采用SPSS 16.0统计软件进行处理,计数资料用χ2检验及Fisher精确检验;计量资料用均数±标准差( ±s)或中位数(四分位数间距)[M(IQR)]表示,用t检验或Mann-Whithey法进行统计分析。初级及次级通畅率用Kaplan-Meier生存分析、Log-rank检验。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

±s)或中位数(四分位数间距)[M(IQR)]表示,用t检验或Mann-Whithey法进行统计分析。初级及次级通畅率用Kaplan-Meier生存分析、Log-rank检验。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1 患者基本临床特征

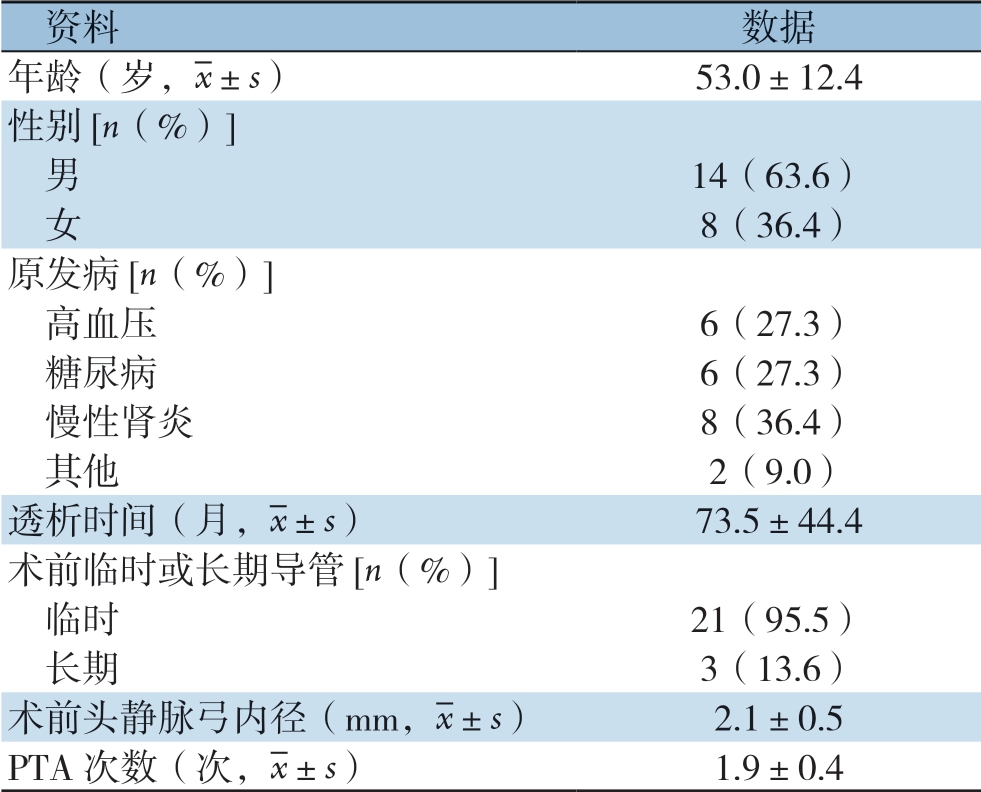

22例患者透析时间较长,达到(73.5±44.4)个月。其中21例患者既往曾行临时导管植入,3例患者既往行长期导管植入;人均接受PTA(1.9±0.4)次(表1)。

表1 患者基本临床特征

Table 1 General information of the patients

资料数据年龄(岁,images/BZ_15_1000_2138_1036_2179.png±s)53.0±12.4性别[n(%)]男14(63.6) 女8(36.4)原发病[n(%)]高血压6(27.3) 糖尿病6(27.3) 慢性肾炎8(36.4) 其他2(9.0)透析时间(月,images/BZ_15_1000_2138_1036_2179.png±s)73.5±44.4术前临时或长期导管[n(%)]临时21(95.5) 长期3(13.6)术前头静脉弓内径(mm,images/BZ_15_1000_2138_1036_2179.png±s)2.1±0.5 PTA次数(次,images/BZ_15_1000_2138_1036_2179.png±s)1.9±0.4

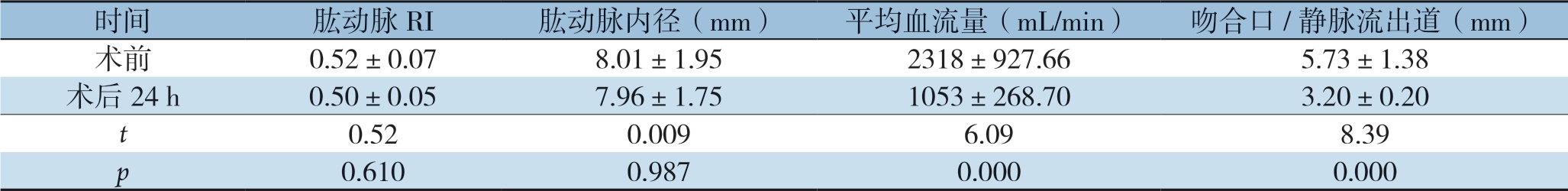

2.2 术前及术后24 h超声血流动力学指标

患者肱动脉阻力指数(resistance index,RI)及肱动脉内径在手术前后均无统计学差异(均P>0.05)。但术后肱动脉平均血流量及吻合口/静脉流出道内径均明显下降(均P<0.05)(表2)。

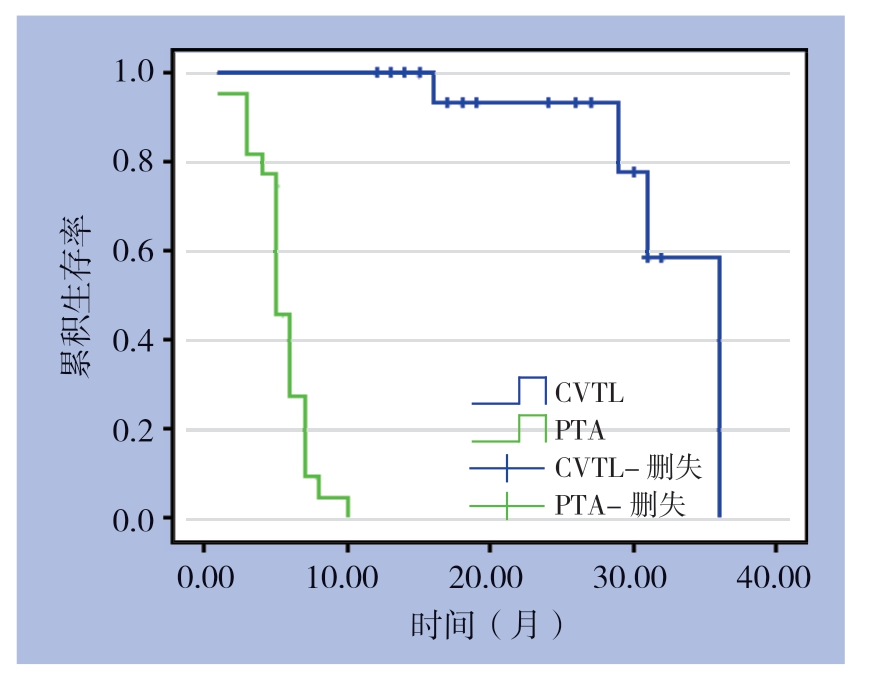

2.3 AVF初级及次级通畅率

BCF合并CAS患者行头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位联合内瘘缩窄术后,平均随访时间21.5(12~36)个月。内瘘初级通畅率(生存分析法)明显高于单纯PTA时(χ2=49.23,P=0.000)(图1)。次级通畅率:截至2018年8月31日,所有患者的BCF内瘘继续使用,随访期间有3例分别在术后16、19、36个月进行第二次内瘘缩窄手术,1例在术后24个月行PTA治疗,解决头静脉-贵要静脉吻合口后方静脉流出道狭窄问题。次级通畅率为6、12、24、36个月均为100%。

表2 术前与术后24 h超声内瘘血流动力学指标比较( ±s)

±s)

Table 2 Comparison of the hemodynamics of BCF measured by Doppler ultrasound before and 24 h aft er operation ( ±s)

±s)

时间肱动脉RI肱动脉内径(mm)平均血流量(mL/min)吻合口/静脉流出道(mm)术前0.52±0.078.01±1.952318±927.66 5.73±1.38术后24 h0.50±0.057.96±1.751053±268.703.20±0.20 t 0.520.0096.098.39 p 0.6100.9870.0000.000

图1 患者行PTA及行头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位联合内瘘缩窄术的初级通畅率

Figure 1 Primary patency rates of the patients undergoing PTA and transposition of the cephalic vein to the basilic or axillary vein plus arteriovenous fi stula constriction

2.4 不良反应及处理

术后1周内有2例出现较明显皮下血肿,以观察为主,未做特殊处理;围手术期及随访期间无血栓事件发生。

3 讨 论

BCF易发生内瘘高流量,导致心输出量过大、通路相关性肢体缺血、内瘘瘤样扩张、甚至内瘘失功等严重并发症[10-14]。CAS是BCF瘘失功的常见原因[1-2]。目前CAS常选用的治疗方案为PTA[1],但因头静脉弓的特殊部位及结构,常需使用高压球囊,发生破裂的风险也高于内瘘其他部位,而且远期通畅率相对较低[15-19]。考虑到CAS的发病机理中,除特殊的解剖学原因外,血流动力学异常如低壁切应力及高流量也是重要原因[13,20-22]。因此限流/缩窄手术降低内瘘高流量也成为治疗CAS的方法之一。

目前常用的限流/缩窄手术方法包括切开血管及不切开血管两大类。不切开血管的方法是在血管壁外用材料(如补片、人工血管材料、丝线等)绑定[10,23-24],其中Miller技术[25-26]因其微创,简单及缩窄尺寸可控被广泛应用。但该方法会有绑定材料(补片及人工血管材料)较难获取,或者价格较高(Miller技术需要用球囊扩张导管)的问题。而且,对于高流量的高位瘘患者,绑定后血管壁被皱缩在绑定材料内,对于已有明显血管扩张如瘤样扩张、血管壁钙化、血管壁不均匀增厚的患者,有可能增加血管狭窄,血栓形成以及假性动脉瘤[27]的风险。研究[25-26]报道他们在平均11个月的随访过程中,通路高流量患者绑定后需要接受血管腔内治疗频率为3.53次/年,自体内瘘采用Miller术的血栓风险为0.2/年。另一种缩窄技术是需要切开血管,手术如果在原部位会因疤痕粘连及血管扭曲等增加手术难度的风险,对于缩窄的血管尺寸掌握也有一定困难。本文中的患者因同时进行头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位,在游离近心端贵要(腋)静脉时会提前游离近心端肱动脉(或腋动脉),在缩窄内瘘时如有必要会暂时阻断近心端动脉,这样,降低游离吻合口的难度,一般不需要游离吻合口近心端及远心端肱动脉,直接在吻合口后方1~2 cm范围内切开静脉流出道,并用外径2.9~3.5 mm的导尿管标定拟缩窄的血管尺寸进行缩窄,不需要使用扩张球囊导管。笔者的方法在术后平均21.5个月的随访中,22例患者中有4例进行了再次干预,无血栓或血管破裂事件发生。再次干预及血栓风险明显低于Miller术式。

本组患者术前肱动脉内径平均(8.01±1.95)mm,平均血流量(2 318±927.66)mL/min,明显超过未做内瘘前的动脉及静脉内径及流量。术后24 h超声复测血流量下降至(1 053±268.7)mL/min,血流量下降超过50%,后方1~2 cm范围内静脉流出道内径(3.2±0.2)mm。在没有改变流入道动脉内径仅缩窄瘘口及静脉流出道情况下达到我们预期的水平,证明该方法有效且可控。术后除两例患者有皮下血肿外,其余均无明显并发症,且随访期间无患者出现缩窄处远心端瘤样扩张,或血栓事件发生。此种缩窄术有较好的安全性。

近几年也有学者[2,11,28-29]认为,在CAS的治疗策略中,头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位术可以作为部分患者的选择。笔者将限流术与头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位术联合,内瘘的12、24、36个月初级通畅率分别为100%、93.3%、58.3%;而之前本组患者接受了平均(1.9±0.4)次的PTA,PTA的6、12个月初级通畅率只有45.5%及0。文献报道单纯行PTA的初级通畅率6个月为42%~46%[15-19];单纯限流术治疗CAS的初级通畅率6个月为76%,12个月为57%[30];单纯行头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位的初级通畅率6个月为77.5%,12个月为66.1%~79%[11,29]。因此,头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位联合内瘘缩窄术同时解决高流量及回流静脉通路狭窄的问题,在随后的平均21.5个月的随访中,患者通路的初级通畅率明显高于前期同组患者单纯行PTA,也高于既往文献报道的单纯限流术或单纯头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位术。次级通畅率6、12、24、36个月均达到100%,效果良好,降低后期干预风险。

本组患者术前头静脉弓的平均内径为(2.1±0.5)mm,虽然高于超声判定显著性狭窄的残余管径2 mm的标准[7-9]。但对于已经出现流入道动脉及静脉流出道均明显扩张的BCF这种高流量的血管通路而言,在已经出现临床症状时应积极干预,主要参考的干预依据是血管狭窄比及临床症状,在狭窄比>50%,且合并有症状时就考虑处理,提高通路的通畅率。

总之,本组病例采用头静脉-贵要(腋)静脉转位联合内瘘缩窄术治疗高流量BCF合并CAS患者,在平均21.5个月的随访期间取得了较好的初级通畅率及次级通畅率,未发生血栓等并发症,减少了通路干预次数及风险。因此,该方法安全、有效、可控,但需要更大样本量的观察。

[1]Asif A, Agarwal AK, Yevzlin A, et al. et al. Interventional Nephrology[M]. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2012.

[2]Kim SM, Yoon KW, Woo SY, et al. Treatment Strategies for Cephalic Arch Stenosis in Patients with Brachiocephalic Arteriovenous Fistula[J]. Ann Vasc Surg, 2019, 54:248-253. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2018.04.037.

[3]Bourquelot P, Stolba J. Surgery of vascular access for hemodialysis and central venous stenosis[J]. Nephrology, 2001, 22(8):491-494.

[4]Patel MS, Davies MG, Nassar GM, et al. Open repair and venous inflow plication of the arteriovenous fistula is effective in treating vascular steal syndrome[J]. Ann Vasc Surg, 2015, 29(5):927-933. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2014.12.042.

[5]万恒, 刘灏, 林智琪, 等. 球囊扩张成形术处理透析用动静脉内瘘狭窄性病变及短中期结果[J]. 中国普通外科杂志, 2016, 25(12):1780-1784. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005-6947.2016.12.018.Wan H, Liu H, Lin ZQ, et al. Balloon dilatation angioplasty for stenosis of hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula and its short-and mid-term results[J]. Chinese Journal of General Surgery, 2016, 25(12):1780-1784. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005-6947.2016.12.018.

[6]贺致宾, 张学民, 张小明, 等. 介入导管技术在动静脉内瘘失功治疗中的应用[J]. 中国普通外科杂志, 2015, 24(6):847-851. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005-6947.2015.06.016.He ZB, Zhang XM, Zhang XM, et al. Application of interventional catheterization procedure in arteriovenous fistula dysfunction[J]. Chinese Journal of General Surgery, 2015, 24(6):847-851. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005-6947.2015.06.016.

[7]Ren J, Han X, Liu H, et al. Ultrasonographic assessment of polytetrafluoroethylene upper extremity arteriovenous hemodialysis access: a retrospective analysis of 31 cases[J]. Ther Apher Dial, 2012, 16(6):548-553. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2012.01106.x.

[8]Kudlicka J, Kavan J, Tuka V, et al. More precise diagnosis of access stenosis: ultrasonography versus angiography[J]. J Vasc Access, 2012,13(3):310-314. doi: 10.5301/jva.5000047.

[9]Lomonte C, Meola M, Petrucci I, et al. The key role of color Doppler ultrasound in the work-up of hemodialysis vascular access[J]. Semin Dial, 2015,28(2):211-215. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12312.

[10]Letachowicz K, Kusztal M, Gołębiowski T, et al. External dilator-assisted banding for high-flow hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula[J]. Ren Fail, 2016, 38(7):1067-1070. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2016.1184936.

[11]Sigala F, Saßen R, Kontis E, et al. Surgical treatment of cephalic arch stenosis by central transposition of the cephalic vein[J]. J Vasc Access. 2014,15(4):272-277. doi: 10.5301/jva.5000195.

[12]Jaberi A, Schwartz D, Marticorena R, et al. Risk factors for the development of cephalic arch stenosis[J]. J Vasc Access, 2007, 8(4):287-295.

[13]Boghosian M, Cassel K, Hammes M, et al. Hemodynamics in the cephalic arch of a brachiocephalic fistula[J]. Med Eng Phys, 2014, 36(7):822-830. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2014.03.001.

[14]Kian K, Asif A. Cephalic arch stenosis[J]. Semin Dial, 2008, 21(1):78-82. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00387.x.

[15]Kershen LM, Marichal DA. Endovascular treatment of stent fracture and pseudoaneurysm formation in arteriovenous fistula dialysis access[J]. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent), 2013, 26(1):47-49. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2013.11928916.

[16]Trerotola SO, Kwak A, Clark TW, et al. Prospective study of balloon inflation pressures and other technical aspects of hemodialysis access angioplasty[J]. J Vasc Interv Radiol, 2005, 16(20):1613-1618. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000183588.57568.36.

[17]Rajan DK, Clark TW, Patel NK, et al. Prevalence and treatment of cephalic arch stenosis in dysfunctional autogenous hemodialysis fistulas[J]. J Vasc Interv Radiol, 2003, 14(5):567-573.

[18]Turmel-Rodrigues L, Pengloan J, Baudin S, et al. Treatment of stenosis and thrombosis in haemodialysis fistulas and grafts by interventional radiology[J]. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2000, 15(12):2029-2036. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.12.2029.

[19]Heerwagen ST, Lönn L, Schroeder TV, et al. Cephalic arch stenosis in autogenous brachiocephalic hemodialysis fistulas: results of cutting balloon angioplasty[J]. J Vasc Access, 2010, 11(1):41-45.

[20]Hammes M, Funaki B, Coe F, et al. Cephalic arch stenosis in patients with fistula access for hemodialysis: relationship to diabetes and thrombosis[J]. Hemodial Int, 2008, 12(1):85-89. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2008.00246.x.

[21]Bennett S, Hammes MS, Blicharski T, et al. Characterization of the cephalic arch and location of stenosis[J]. J Vasc Access, 2015, 16(1):13-18. doi: 10.5301/jva.5000291.

[22]Hammes M, Boghosian M, Cassel K, et al. Increased Inlet Blood Flow Velocity Predicts Low Wall Shear Stress in the Cephalic Arch of Patients with Brachiocephalic Fistula Access[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(4):e0152873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152873.

[23]Kok HK, Maingard J, Asadi H, et al. Percutaneous dialysis arteriovenous fistula banding for flow reduction - a case series[J]. CVIR Endovasc, 2018, 1(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s42155-018-0035-z.

[24]Kanno T, Kamijo Y, Hashimoto K, et al. Outcomes of blood flow suppression methods of treating high flow access in hemodialysis patients with arteriovenous fistula[J]. J Vasc Access, 2015, 16(Suppl 10):S28-33. doi: 10.5301/jva.5000415.

[25]Goel N, Miller GA, Jotwani MC, et al. Minimally Invasive Limited Ligation Endoluminal-assisted Revision (MILLER) for treatment of dialysis access-associated steal syndrome[J]. Kidney Int, 2006, 70(4):765-770. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001554.

[26]Miller GA, Goel N, Friedman A. et al. The MILLER banding procedure is an effective method for treating dialysis-associated steal syndrome[J]. Kidney Int, 2010, 77(4):359-366. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.461.

[27]Mallios A, Boura B, Costanzo A, et al. Pseudo-aneurysm caused from banding failure[J]. J Vasc Access, 2018, 19(4):392-395. doi: 10.1177/1129729817747544.

[28]Sivananthan G, Menashe L, Halin NJ. Cephalic arch stenosis in dialysis patients: review of clinical relevance, anatomy, current theories on etiology and management[J]. J Vasc Access, 2014, 15(3):157-162. doi: 10.5301/jva.5000203.

[29]Jang J, Jung H, Cho J, et al. Central Transposition of the Cephalic Vein in Patients with Brachiocephalic Arteriovenous Fistula and Cephalic Arch Stenosis[J]. Vasc Specialist Int, 2014, 30(2):62-67. doi: 10.5758/vsi.2014.30.2.62.

[30]Miller GA, Friedman A, Khariton A, et al. Access flow reduction and recurrent symptomatic cephalic arch stenosis in brachiocephalic hemodialysis arteriovenous fistulas[J]. J Vasc Access, 2010, 11(4):281-287.