大多数胰腺癌患者在初诊时已进入晚期,导致只有不到20%的患者能够手术切除,并且术后容易复发[1]。此外,胰腺癌5年生存率不到5%,预计到2030年,胰腺癌将成为恶性肿瘤中的第2位致死原因[2-4]。可见,胰腺癌具有重要早期症状隐匿、进展快、预后差等特点。而可靠的预后指标对掌握胰腺癌患者的病情,制定有效的临床治疗策略非常重要。但目前,肿瘤大小、组织学分级及组织学分型等指标对胰腺癌患者预后的价值有限[5]。众多研究显示,炎症在肿瘤的发生发展中起着至关重要的作用,是公认的癌症标志之一[6-8]。系统免疫炎症指数(systemiCImmune-inflammation index,SII)被定义为(血小板计数×中性粒细胞计数)/淋巴细胞计数[9],已被证明是肝细胞癌和肺癌等恶性肿瘤的独立的预后因素[10-11]。现阶段,多数研究者认为SII升高可预测胰腺癌患者的预 后[12-13],但张水生[14]调整性别、年龄、肿瘤位置和TNM分期等混杂因素后发现SII升高并不是胰腺癌患者OS的独立危险因素。可见,SII对胰腺癌患者预后的价值仍存在争议。因此,本研究采用Meta分析方法,系统地探讨SII对胰腺癌的预后意义,以期为改善预后和个体化治疗提供证据。

1 资料与方法

1.1 纳入与排除标准

1.1.1 纳入标准(1) 研究类型:队列研究或病例-对照研究;(2) 研究对象:病理诊断为胰腺癌的患者;(3) 结局指标 :至少包括总体生存期(overall survival,OS)、癌症特异性生存期(cancerspecific survival,CSS)和无病生存期(disease-free survival,DFS)其中之一。

1.1.2 排除标准(1) 文章类型为综述、系统评价、会议论文;(2) 无法获得该文献的全文;(3) 数据不足;(4) 重复发表文献;(5) 非中、英文文献。

1.2 搜索策略

计算机检索Pub Med、Embase、Web of Science、Medline、Cochrane Library、CNKI、CBM、WanFang Data和VIP数据库,收集从建库到2020年3月公开发表的有关SII与胰腺癌预后关系的队列和病例-对照研究研究。检索采用主题词与自由词相结合的方式进行。并且,追溯已纳入文献的参考文献,以获取相关文献。中文检索词包括:“胰腺癌 ”、“胰腺肿瘤”、“系统免疫炎症指数”、“全身免疫炎症指数”和“SII”。英文检索词包括:Pancreatic、Pancreas、Tumor、Cancer、Car CInoma、Neoplasm、Systemi CImmune-Inflammation Index、SII。

1.3 文献筛选和资料提取

由2 名研究者独立筛选了文献和提取资料并交叉核对。通过双方讨论或与第3位研究者协商解决争议。文献筛选时首先阅读题目及摘要,在排除明显不相关的文献后,进一步阅读全文确定是否纳入。如有需要,通过邮件、电话联系原始研究作者获取未确定但对本研究非常重要的信息。资料提取内容包括:研究题目、第一作者、出版年份、研究时间、国家、样本量、性别、治疗方式、OS/DFS/CSS风险比(HR)、随访时间、SII临界值、SII选取时间点、分期。

1.4 纳入研究质量评价

由2名研究人员独立根据纽卡斯尔-渥太华量表(Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Scale,NOS)对纳入研究进行偏倚风险评价,得分为6分或更高的研究被定义为高质量研究[15]。

1.5 统计学处理

采用Stata 12.0软件进行分析数据。结合95%置信区间(CI)的危险比(HR)来评估SII与PC患者预后的关系。在研究之间使用I2统计量和q检验来评估异质性。当P<0.1和(或)I2>50%,异质性显著,采用随机效应模型进行Meta分析;否则,采用固定效应模型进行Meta分析[16]。对潜在发表偏倚进行Begg检验和Egger检验(检验水准为P=0.05)[17]。

2 结 果

2.1 文献检索结果与纳入研究的特点

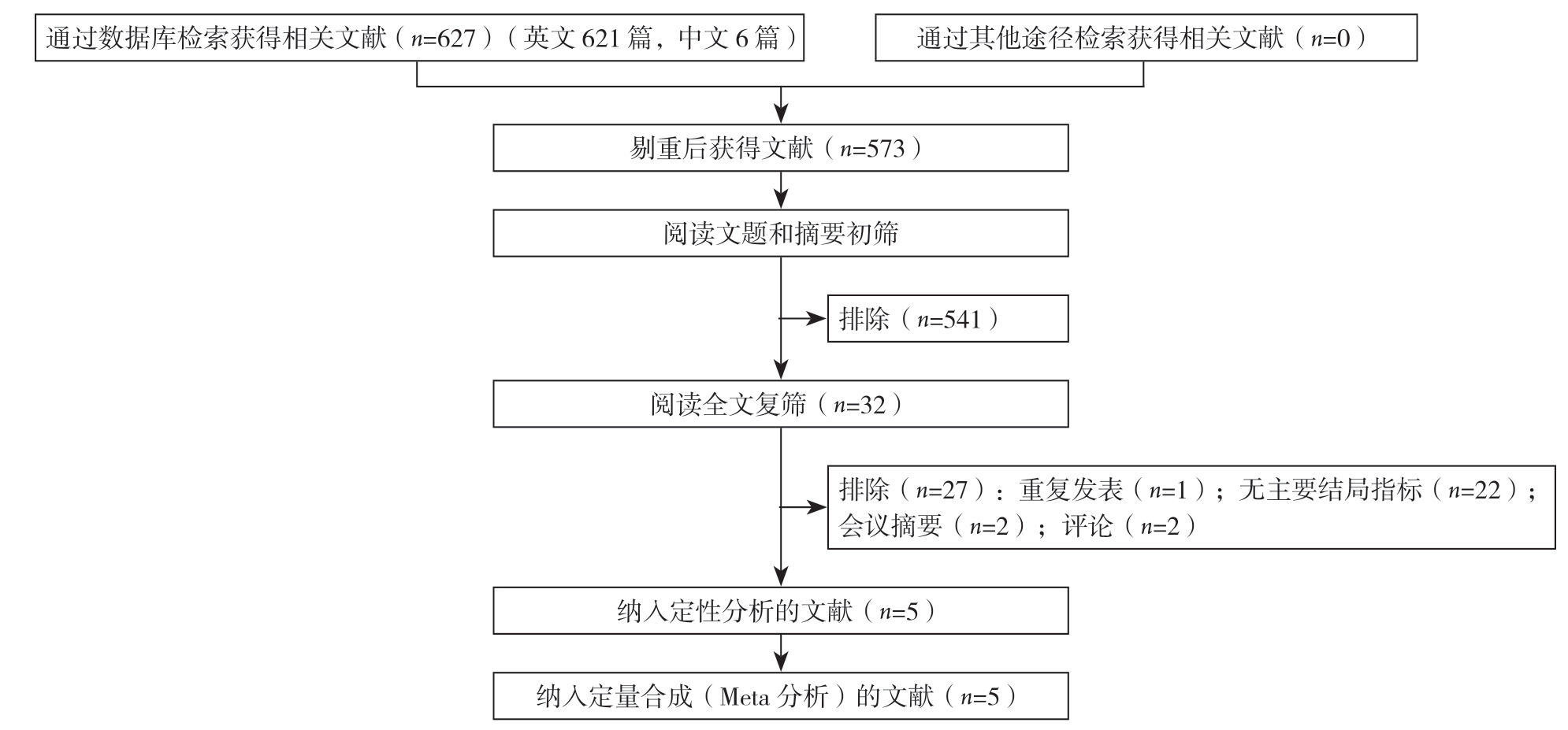

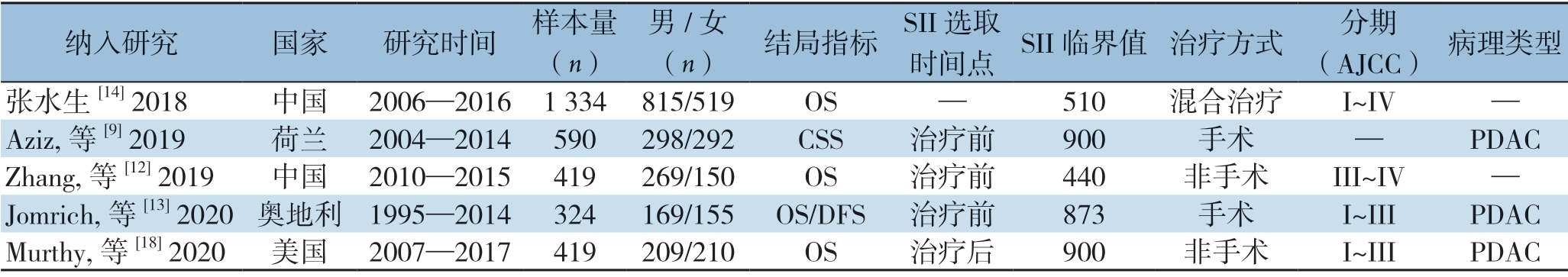

初检共获取相关文献627篇,经过筛选,最终纳入5项队列研究[9,12-14,18](图1)。纳入研究发表于2018—2020年,其中2项在中国进行,另外3项分别在美国、奥地利和荷兰进行。4项研究[12-14,18]报道了SII与OS的关系,1项研究报道了SII与DFS的关系,另外一项研究[9]报道了SII与CSS之间的关系(表1)。基于NOS量表,对纳入研究的质量评估发现,得分在6分以上,所有研究均被认为是高质量研究(表2)。

图1 文献筛选流程及结果

Figure 1 Literature screening process and results

表1 纳入研究的基本特征

Table 1 General characteristics of the included studies

纳入研究 国家 研究时间 样本量(n)男/女(n) 结局指标 SII 选取时间点 SII 临界值 治疗方式 分期(AJCC) 病理类型张水生[14] 2018 中国 2006—20161334815/519 OS — 510 混合治疗 I~IV —Aziz, 等[9] 2019 荷兰 2004—2014590 298/292 CSS 治疗前 900 手术 — PDAC Zhang, 等[12] 2019 中国 2010—2015419 269/150 OS 治疗前 440 非手术 III~IV —Jomrich, 等[13] 2020 奥地利 1995—2014324 169/155 OS/DFS 治疗前 873 手术 I~III PDAcmurthy, 等[18] 2020 美国 2007—2017419 209/210 OS 治疗后 900 非手术 I~III PDAC

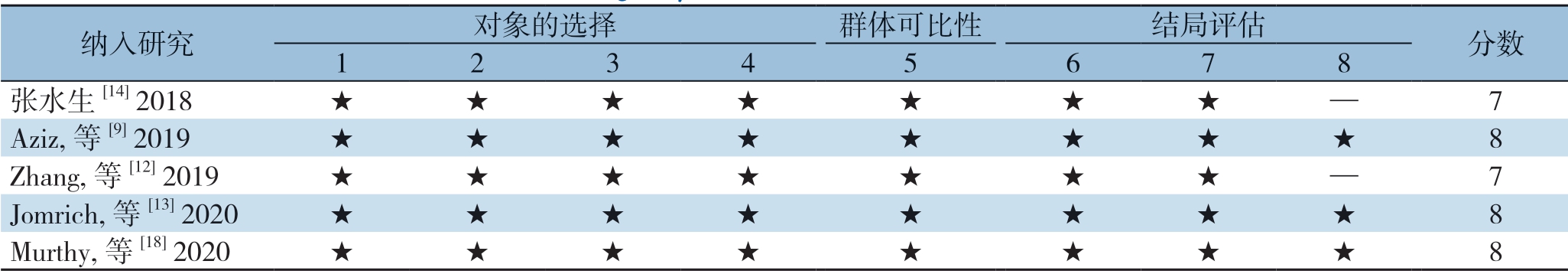

表2 纳入研究的质量评价表

Table 2 Quality assessment of the included studies

注:★表示为1 分;1 为暴露队列的代表性;2 为非暴露队列的选择;3 为暴露因素确定;4 为研究起始前尚无要观察的结局事件;5 为基于设计或分析所得的队列的可比性;6 为结局事件的评价;7 为随访时间足够长;8 为随访的完整性

Note: One asterisk standing for 1 score; 1 representing the representativeness of the exposed cohort; 2 representing the selection of nonexposed cohort; 3 representing the determination of the exposure factors; 4 representing no outcome events requiring observation from the beginning of the study; 5 representing comparability across cohorts based on the design or analysis; 6 representing the assessment of the outcome events; 7 representing enough follow-up time; 8 representing the integrity of blinded follow-up examinations

纳入研究 对象的选择 群体可比性 结局评估 分数1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8张水生[14] 2018 ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ — 7 Aziz, 等[9] 2019 ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ 8 Zhang, 等[12] 2019 ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ — 7 Jomrich, 等[13] 2020★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ 8 Murthy, 等[18] 2020★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ 8

2.2 Meta 分析结果

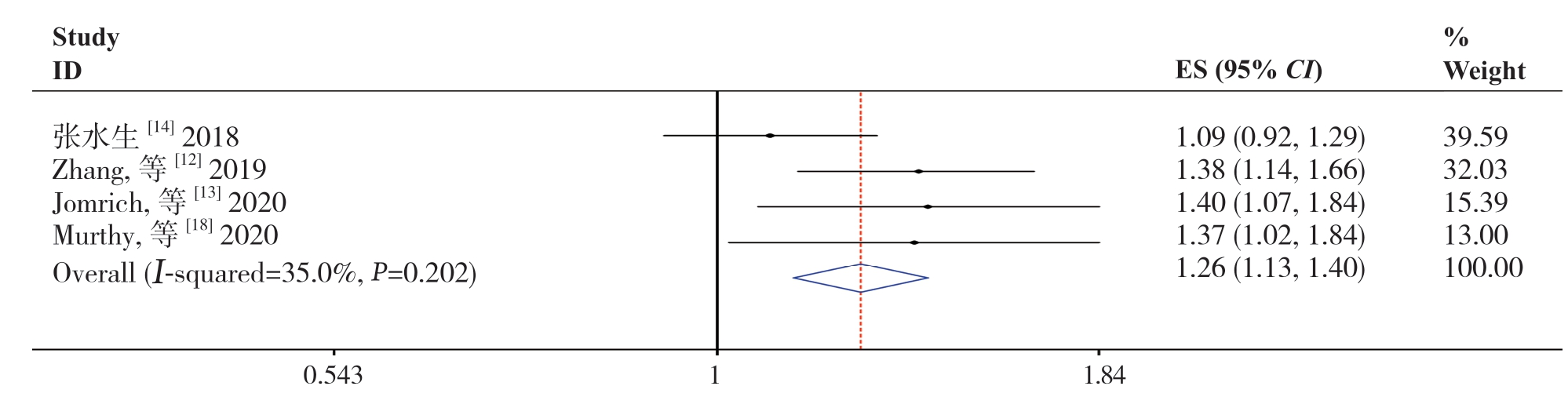

2.2.1 SII 与OS 的关系 有4项研究[12-14,18] 报道了SII 与OS 之间的关系,研究间无明显异质性(I2=35.0%,P=0.202),故采用固定效应模型。Meta 分析结果表明,高SII 值患者的OS 缩短(HR=1.26,95% CI=1.13~1.40,P<0.001)(图2)。

2.2.2 SII 与DFS、CSS的关系 1项研究[9] 报道了高SII患者CSS较差(HR=2.32,95% CI=1.55~3.48,P<0.001);另1 项研究[12]报道SII 与DFS 无明显关系(HR=1.27,95% CI=0.95~1.70,P<0.106)。

图2 SII 与OS 关系的Meta 分析

Figure 2 Meta-analysis of relationship between SII and OS

2.3 亚组分析

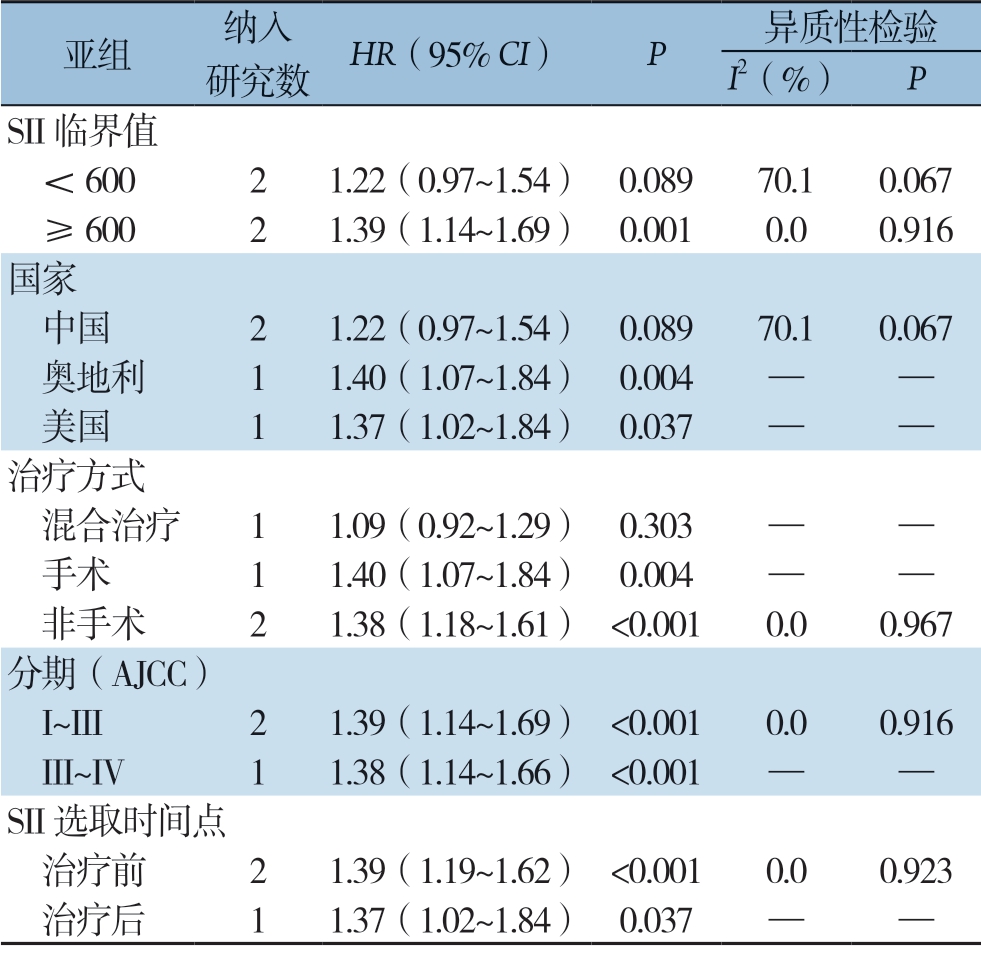

为了进一步探讨SII的预后价值,从SII临界值 、国家、治疗方式、分期和SII选取时间点等方面进行亚组分析。亚组分析发现,SII临界值≥600 时,高SII与OS 缩短有关(HR=1.39,95% CI=1.14 ~1.69,P=0.001),而SII临 界值<600 时,SII与OS 无明显关系(HR=1.22,95% CI=0.97 ~1.54,P=0.089)。来自奥地利(HR=1.40,95% CI=1.07~1.84,P=0.016)和美国(HR=1.37,95% CI=1.02~1.84,P=0.004)的研究显示高SII与OS 缩短有关,而中国的研究SII与OS 无明显关系(HR=1.22,95% CI=0.97~1.54,P=0.089)。治疗方式中,手术治疗(HR=1.40,95% CI=1.07~1.84,P=0.004)和非手术治疗(HR=1.38,95% CI=1.18~1.61,P<0.001)患者高SII与OS缩短有关;而混合治疗患者中SII与OS无明显相关性(HR=1.09,95% CI=0.92 ~1.29,P=0.303)。AJCC分期(I ~III)(HR=1.39,95% CI=1.14 ~1.69,P <0.001)和A JC C 分期(III ~IV)(HR=1.38,95% CI=1.14~1.66,P<0.001)高SII均与OS缩短有关。SII选取时间点上,治疗前(HR=1.39,95% CI=1.19~1.62,P<0.001)和治疗后(HR=1.37,95% CI=1.02 ~1.84,P=0.037)高SII均与OS缩短有关(表3)。

2.4 发表偏倚

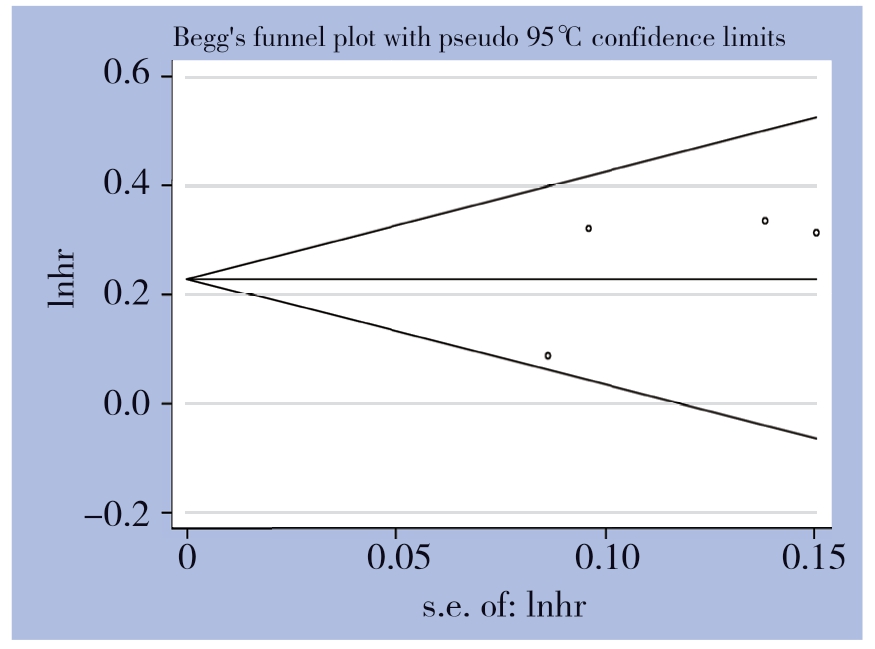

发表偏倚通过Begg检验和Egger检验进行评估。Begg检验(Z=0.34,P=1.000)和Egger's检验(t=1.19,P=0.356)结果表明,纳入文献存在发表偏倚的可能性较小(图3)。

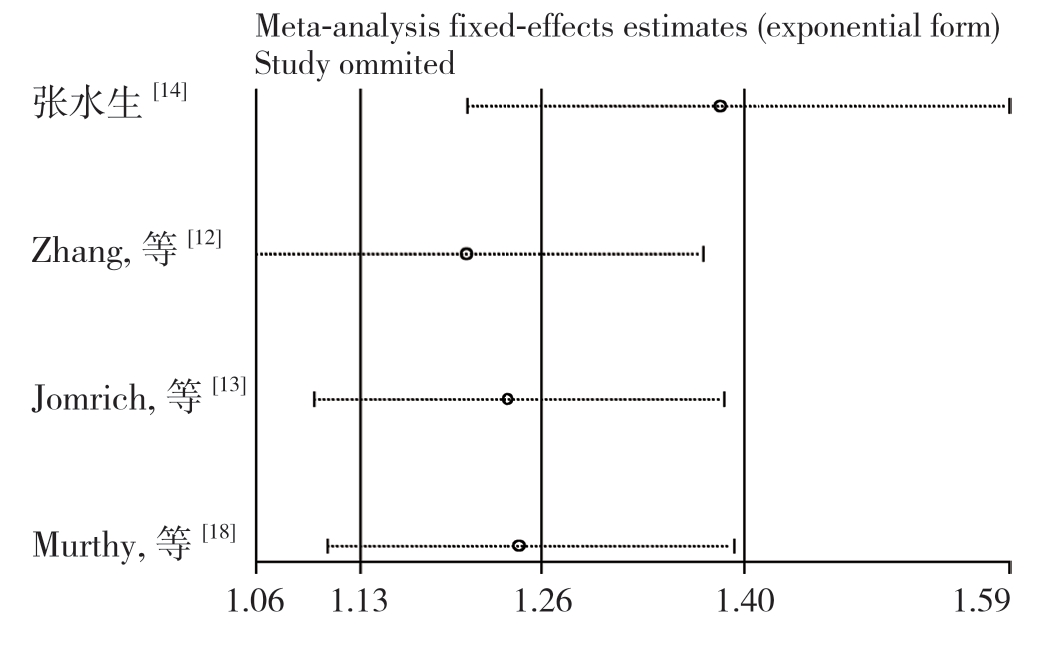

2.5 敏感度分析

采用依次剔除单个研究的方法进行敏感性分析,敏感度分析结果显示Meta 分析结果稳定(HR=1.21~1.38)(图4)。

表3 亚组分析

Table 3 Subgroup analysis

亚组 纳入研究数 HR(95% CI) P 异质性检验I2(%) PSII 临界值 <600 2 1.22(0.97~1.54) 0.089 70.1 0.067 ≥600 2 1.39(1.14~1.69) 0.001 0.0 0.916国家 中国 2 1.22(0.97~1.54) 0.089 70.1 0.067 奥地利 1 1.40(1.07~1.84) 0.004 — — 美国 1 1.37(1.02~1.84) 0.037 — —治疗方式 混合治疗 1 1.09(0.92~1.29) 0.303 — — 手术 1 1.40(1.07~1.84) 0.004 — — 非手术 2 1.38(1.18~1.61) <0.001 0.0 0.967分期(AJCC) I~III 2 1.39(1.14~1.69) <0.001 0.0 0.916 III~IV 1 1.38(1.14~1.66) <0.001 — —SII 选取时间点 治疗前 2 1.39(1.19~1.62) <0.001 0.0 0.923 治疗后 1 1.37(1.02~1.84) 0.037 — —

图3 SII 与OS 关系的Begg 检验

Figure 3 Begg’s test of relationship between SII and OS

图4 SII 与OS 关系的敏感度分析

Figure 4 Sensitivity analysis of relationship between SII and OS

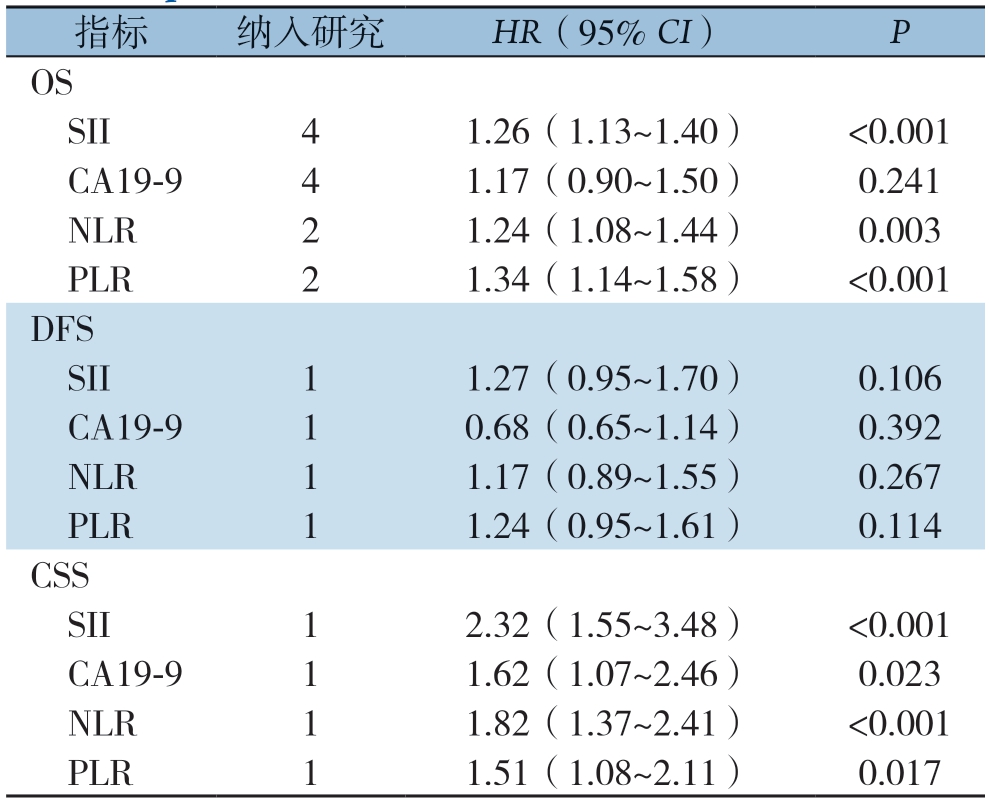

2.6 SII 与其他预测指标

研究结果表明,SII、中性粒细胞与淋巴细胞比值(NLR)和血小板与淋巴细胞比值(PLR)对胰腺癌患者OS有预测作用,而C19-9对OS无预测作用;4种预测指标对DFS均无预测作用,而对CSS有预测作用(表4)。

表4 SII、CA19-9、NLR 和PLR 在胰腺癌的预后价值

Table 4 Prognostic values of SII, CA19-9, NLR and PLR in pancreatic cancer

指标 纳入研究 HR(95% CI) P OS SII 4 1.26(1.13~1.40) <0.001 CA19-9 4 1.17(0.90~1.50) 0.241 NLR 2 1.24(1.08~1.44) 0.003 PLR 2 1.34(1.14~1.58) <0.001 DFS SII 1 1.27(0.95~1.70) 0.106 CA19-9 1 0.68(0.65~1.14) 0.392 NLR 1 1.17(0.89~1.55) 0.267 PLR 1 1.24(0.95~1.61) 0.114 CSS SII 1 2.32(1.55~3.48) <0.001 CA19-9 1 1.62(1.07~2.46) 0.023 NLR 1 1.82(1.37~2.41) <0.001 PLR 1 1.51(1.08~2.11) 0.017

3 讨 论

本研究目的为系统评价SII与胰腺癌患者预后之间的关系,共纳入5 项回顾性队列研究,包括3086例患者。为充分利用纳入研究数据,本研究根据纳入文献特征对SII临界值、国家、治疗方式、AJCC分期和SII选取时间点等方面进行了亚组分析;通过逐一剔除单项研究进行敏感性分析;采用Begg's 检验和 Egger's检验对纳入研究进行发表偏倚评价;且纳入研究NOS评分在7~8分之间,提示纳入研究整体质量较高。本研究设计合理、纳入研究质量较高,结论具有较高的可靠性与科学性。

最近一项在乳腺癌患者中涉及2642例患者的8项研究的Meta分析显示,较高的SII与较差的OS相关,并且SII的高低与一些临床病理特征相关[19]。本研究结果显示,SII升高与胰腺癌患者预后相关,这与之前对其他癌症的研究的Meta分析一致,SII升高可能是胰腺癌预后的一个独立危险因素。但本研究中由于受纳入研究较少的限制,未能分析SII与临床病理特征的关系。亚组分析结果显示,SII临界值≥600时,SII较高与OS缩短有关;但SII临界值<600时,SII与OS无明显关系;报道成年人SII参考区间为110.91~783.00,这可能是由于选取的SII临界值选取包含于正常范围内,造成偏倚[20]。根据不同国家进行亚组分析,结果显示在奥地利和美国SII较高与OS缩短相关,但在中国SII与OS无明显相关;这提示可能与种族有关,但还需要高质量研究来证实。手术治疗和非手术治疗SII较高都与OS缩短相关;但混合治疗SII与OS无明显关系。对AJCC分期进行亚组分析,I~III期和III~IV期的患者SII较高都与OS缩短有关。对SII选取时间点进行亚组分析,治疗前和治疗后SII较高都与OS缩短有关。此外,本研究发现,SII、NLR和PLR对胰腺癌患者OS有预测作用,这与以往研究[21-22]报道一致。而CA19-9对胰腺癌患者OS无预测作用,与Asaoka等[22]报道结果不一致,这可能是由于本研究纳入文献较少,造成偏倚。

肿瘤微环境近年来收到越来越多的关注,而炎症细胞是肿瘤微环境的重要组成部分。炎症在肿瘤的生长、进展和转移中起着至关重要的作用,是肿瘤的主要特征之一 [23-24]。SII是以外周血淋巴细胞、中性粒细胞和血小板计数为基础,是NLR与PLR的结合,能充分反映免疫与炎症的平衡关系[25-27]。中性粒细胞和血小板的促肿瘤功能以及淋巴细胞的抑瘤作用也许能解释SII升高在癌症中的预后价值。中性粒细胞和血小板增多症与癌症前效应有关[28-31]。中性粒细胞可以激活内皮细胞和实质细胞,从而促进循环肿瘤细胞的转移[32]。中性粒细胞也通过分泌炎症介质来介导癌细胞的增殖和转移[33]。血小板可以释放多种促进癌细胞增殖的生长因子[34]。此外,血小板还可以保护循环肿瘤细胞免受抗肿瘤免疫反应的影响,例如,在胰腺癌中,血小板可增加肿瘤细胞黏附能力以逃避宿主的免疫监测[35-37],从而促进肿瘤细胞的血管生成和转移。淋巴细胞在机体对恶性肿瘤的免疫应答中起着重要的作用,可抑制肿瘤细胞增殖和迁移,已有研究发现淋巴细胞减少与一些恶性肿瘤患者生存不良有关[38-40]。值得期待的是,SII可通过血液检测,具有高效、方便、经济等优势,可帮助临床医生迅速、便捷地预测患者预后,从而尽早为其制定合理的治疗策略。

本研究也存在一定的局限性。首先,这些纳入的文章中存在一些异质性,我们采用了亚组分析等方法,但仍未能探究所有的异质性;其次,纳入研究较少,亚组分析纳入的研究较少,影响了结果的准确性。第三,SII的最佳分界值还没有统一的标准,且容易受到患者自身情况的影响,如感染、化疗等。

综上所述,目前的证据表明,SII可以作为PC患者的一个有用的预后指标。但是由于纳入研究的数量和质量的限制,上述结论还需要更多高质量、大样本研究的验证。

[1] 武赞凯, 杜恒锐, 王振江, 等.胰腺癌流行病学及诊治的研究进展[J].中南大学学报: 医学版, 2017, 42(6):713-719.doi:10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2017.06.018.

Wu ZK, Du HR, Wang ZJ, et al.Research progress in epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment for pancreatic cancer[J].Journal of Central South University(Medical Science), 2017, 42(6):713-719.doi:10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2017.06.018.

[2] Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A.Cancer statistics, 2018[J].CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(1):7-30.doi: 10.3322/caac.21442.

[3] Saad AM, Turk T, Al-Husseini MJ, et al.Trends in pancreatic adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality in the United States in the last four decades: a SEER-based study[J].BMC Cancer, 2018, 18(1):688.doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4610-4.

[4] Jemal A, Ward EM, Johnson CJ, et al.Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2014, Featuring Survival[J].J Natl Cancer Inst, 2017, 109(9):djx030. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx030.

[5] Fesinmeyer MD, Austin MA, Li CI, et al.Differences in survival by histologic type of pancreatic cancer[J].Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2005, 14(7):1766-1773.doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0120.

[6] Candido J, Hagemann T.Cancer-related inflammation[J].J Clin Immunol, 2013, 33(Suppl 1):S79-84.doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9847-0.

[7] GrivennikovsI, Greten FR, Karin M.Immunity, inflammation, and cancer [J].Cell, 2010, 140(6):883-899.doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025.

[8] Toria N, Kikodze N, Rukhadze R, et al.Inflammatory biomarkers in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a retrospective study[J].Georgian Med News, 2020, (299):21-26.

[9] Aziz MH, Sideras K, Aziz NA, et al.The Systemic-immuneinflammation Index Independently Predicts Survival and Recurrence in Resectable Pancreatic Cancer and its Prognostic Value Depends on Bilirubin Levels A Retrospective Multicenter Cohort Study[J].Ann Surg, 2019, 270(1):139-146.doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002660.

[10] Wang B, Huang Y, Lin T.PrognostiCImpact of elevated pretreatment systemiCImmune-inflammation index (SII) in hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis[J].Medicine (Baltimore), 2020, 99(1):e18571.doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018571.

[11] Wang Y, Li Y, Chen P, et al.Prognostic value of the pretreatment systemiCImmune-inflammation index (SII) in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis[J].Ann Transl Med, 2019, 7(18):433.doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.08.116.

[12] Zhang K, Hua YQ, Wang D, et al.SystemiCImmune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer[J].J Transl Med, 2019, 17(1):30.doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1782-x.

[13] Jomrich G, Gruber ES, Winkler D, et al.SystemiCImmune-Inflammation Index (SII) Predicts Poor Survival in Pancreatic Cancer Patients Undergoing Resection[J].J Gastrointest Surg, 2020, 24(3):610-618.doi: 10.1007/s11605-019-04187-z.

[14] 张水生.胰腺癌临床病理特点及预后/Hsa_circ_0007564: 胰腺癌诊断和预后新的标志物[D].北京: 北京协和医学院, 2018.

Zhang SS.Clinicopathological features and outcomes of pancreatic cancer/Hsa_circ_0007564: a novel diagnostic and prognosticmarker for pancreatic cancer[D].Beijing: Peking Union Medical College, 2018.

[15] Stang A.Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in metaanalyses[J].Eur J Epidemiol, 2010, 25(9):603-605.doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z.

[16] Barili F, Parolari A, Kappetein P A, et al.Statistical Primer: heterogeneity, random- or fixed-effects model analyses?[J].Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg, 2018, 27(3):317-321.doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivy163.

[17] Herrmann D, Sinnett P, Holmes J, et al.Statistical controversies in clinical research: publication bias evaluations are not routinely conducted in clinical oncology systematic reviews [J].Ann Oncol, 2017, 28(5):931-937.doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw691.

[18] Murthy P, Zenati M S, Al Abbas AI, et al.Prognostic Value of the SystemiCImmune-Inflammation Index (SII) After Neoadjuvant Therapy for Patients witHResected Pancreatic Cancer[J].Ann Surg Oncol, 2020, 27(3):898-906.doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-08094-0.

[19] Zhang Y, Sun Y, Zhang Q.Prognostic value of the systemiCImmune-inflammation index in patients witHBreast cancer: a meta analysis[J].Cancer Cell Int, 2020, 20:224.doi: 10.1186/s12935- 020-01308-6.

[20] 余建洪, 刘钰.自贡地区成人外周血SII、NLR、d-NLR、PLR及LMR参考区间的建立[J].检验医学, 2019, 34(7):630-632.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-8640.2019.07.013. Yu JH, Liu Y.Establishment of reference intervals for SII, NLR, D-NLR, PLR and LMR in peripheralblood of adults in Zigong District[J].Laboratory Medicine, 2019, 34(7):630-632.doi:10.3969/j.issn.1673-8640.2019.07.013.

[21] Riauka R, Ignatavicius P, Barauskas G.Preoperative Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio as APrognostic Factor for Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis[J].Dig Surg, 2020.doi:10.1159/000508444.[Online ahead of print]

[22] Asaoka T, Miyamoto A, Maeda S, et al.PrognostiCImpact of preoperative NLR and CA19-9 in pancreatic cancer[J].Pancreatology, 2016, 16(3):434-440.doi:10.1016/j.pan.2015.10.006.

[23] Balkwill F, Mantovani A.Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow?[J].Lancet, 2001, 357(9255):539-545.doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0.

[24] Kılınçalp S, Ekiz F, Başar O, et al.Mean platelet volume could be possible biomarker in early diagnosis and monitoring of gastric cancer[J].Platelets, 2014, 25(8):592-594.doi:10.3109/09537104.2013.783689.

[25] Chen L, Yan Y, Zhu L, et al.SystemiCImmune-inflammation index as a useful prognostiCIndicator predicts survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy[J].Cancer Manag Res, 2017, 9:849-867.doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S151026.

[26] Hong X, Cui B, Wang M, et al.SystemiCImmune-inflammation Index, Based on Platelet Counts and Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio, Is Useful for Predicting Prognosis in Small Cell Lung Cancer[J].Tohoku J Exp Med, 2015, 236(4):297-304.doi: 10.1620/tjem.236.297.

[27] Mantovani A, Cassatella MA, Costantini C, et al.Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity[J].Nat Rev Immunol, 2011, 11(8):519-531.doi: 10.1038/nri3024.

[28] Lou XL, Sun J, Gong SQ, et al.Interaction between circulating cancer cells and platelets: clinical implication[J].Chin J Cancer Res,2015, 27(5):450-460.doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2015.04.10.

[29] Ocana A, Nieto-Jiménez C, Pandiella A, et al.Neutrophils in cancer: prognostic role and therapeutic strategies [J].Mol Cancer, 2017, 16(1):137.doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0707-7.

[30] Uribe-Querol E, Rosales C.Neutrophils in Cancer: Two Sides of the Same Coin[J].J Immunol Res, 2015, 2015:983698.doi: 10.1155/2015/983698.

[31] Bambace NM, Holmes CE.The platelet contribution to cancer progression[J].J Thromb Haemost, 2011, 9(2):237-249.doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04131.x.

[32] De Larco JE, Wuertz BR, Furcht LT.The potential role of neutrophils in promoting the metastatic phenotype of tumors releasing interleukin-8[J].Clin Cancer Res, 2004, 10(15):4895-4900.doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0760.

[33] Houghton AM, Rzymkiewicz DM, Ji H, et al.Neutrophil elastasemediated degradation of IRS-1 accelerates lung tumor growth[J].Nat Med, 2010, 16(2):219-223.doi: 10.1038/nm.2084.

[34] Li N.Platelets in cancer metastasis: To help the "villain" to do evil[J].Int J Cancer, 2016, 138(9):2078-2087.doi: 10.1002/ijc.29847.

[35] Shi H, Li J, Fu D.Process of hepaticmetastasis from pancreatic cancer: biology with clinical significance[J].J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2016, 142(6):1137-1161.doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-2024-0.

[36] Stegner D, Dütting S, Nieswandt B.Mechanistic explanation for platelet contribution to cancer metastasis [J].Thromb Res, 2014, 133(Suppl 2): S149-157.doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(14)50025-4.

[37] Franco AT, Corken A, Ware J.Platelets at the interface of thrombosis, inflammation, and cancer [J].Blood, 2015, 126(5):582-588.doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-531582.

[38] Hanahan D, Weinberg RA.Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation[J].Cell, 2011, 144(5):646-674.doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013.

[39] Ray-Coquard I, Cropet C, Van Glabbeke M, et al.Lymphopenia as APrognostic factor for overall survival in advanced carcinomas, sarcomas, and lymphomas[J].Cancer Res, 2009, 69(13):5383-5391.doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3845.

[40] Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD.The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting[J].Immunity, 2004, 21(2):137-148.doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.017.